The Curious Case of Phantom Carbon Credits

Navigating the physical and accounting realms of carbon credits

When we watch a movie, there is an implicit agreement that we are willing to accept the fictional world and characters presented in the film, despite knowing that they are not real.

We call it the suspension of disbelief, which involves temporarily setting aside one's own beliefs and skepticism in order to fully engage with the narrative and enjoy the story.

For instance, you may not believe that someone would be born an old man and start to age backward, but for the sake of the movie, you suspend your disbelief.

What if I told you that this also happens in the world of carbon credits?

If you have been following the news on Shell benefiting from selling ‘phantom credits’ that netted the oil company $200mn, you’ll know what I am talking about.

Let’s begin!

First, some background. This story is about Shell’s Quest carbon capture and storage (CCS) project in Alberta, Canada.

According to this excellent Greenpeace report, the Alberta government released a carbon plan back in 2008 to boost their climate credibility amid rising criticisms over the staggering greenhouse gas emissions from its oil sands.

As part of the plan, the province started a two-billion-dollar fund to encourage companies to build CCS facilities “that would capture and permanently store up to five million tonnes of carbon dioxide per year by 2015”.

Remember that number as it would come into play again in the later part of this story.

Oil giant Shell submitted its Quest proposal, which ultimately received the go-ahead. Construction began in 2012 and the plant began its commercial operations in 2015.

As we all know, such large-scale projects typically carry a high amount of risk and not surprisingly, subsidies are required to jump start these programs.

From the same Greenpeace report:

Shell proposed that government funding be provided upfront rather than spread over the life of the project and that the Government of Alberta not deduct any revenues Shell received from the sale of emissions credits from the amount of the grant.

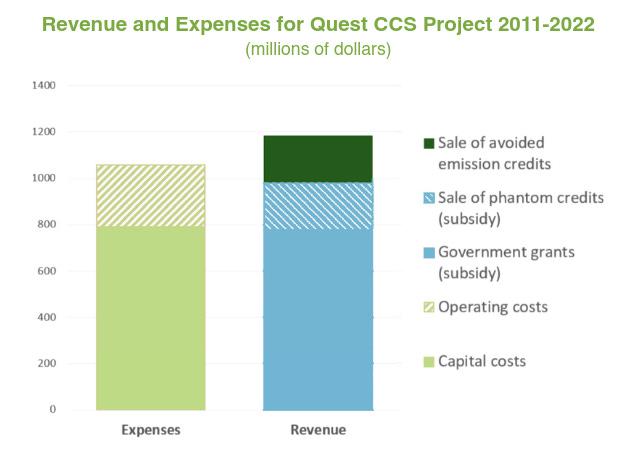

In total from 2009 to 2022, Shell’s Quest received $777 million in subsidies and $406 million from selling carbon credits:

The subsidy bit is fine-ish, because like we said earlier, CCS projects are capital intensive and carry a high execution risk. Furthermore, these projects are not really economically viable with low carbon prices.

The problematic bit came from the sale of credits. Out of the $406 million, approximately 50% of it came from selling phantom credits, which does not directly translate to any emissions.

Where do these phantom credits come from?

Here’s the kicker: documents obtained by Greenpeace reveal that half of those carbon credits were for carbon that was never captured because the Alberta government granted the facility two tons of carbon credits for every ton sequestered underground.

Wait, how do you award credits for carbon that was never captured?

This is where you, the audience, have to suspend your disbelief.

Bloomberg’s Matt Levine shed some light on this with his excellent piece (Here, Have Some Extra Carbon Credits).

In his words, you can think of a carbon credit as [1] one ton of carbon that has been removed from the atmosphere or [2] a “quasi-regulatory accounting quantity”.

In the first approach, carbon credit is a physical thing, whereas in the second approach, it is merely an instrument of accounting, which means it can be created freely by the Alberta government.

Here is a quote from Matt’s piece:

“ … Nobody is buying the credits as a physics experiment; making the quantities balance exactly in physical reality is not the goal.”

That is fine, I guess, and no one is expecting the quantities to balance exactly.

But in this case, we are talking about a one-for-one deal. Essentially, for every ton of carbon sequestered underground, the government/regulator/credit issuer is asking you to just believe that another ton of carbon is being magically removed somewhere.

Even if the accounting credits may not match what is happening in the physical world, it’s fine, comes the assurance. This is for the greater good and once we have the CCU projects up-and-running, the benefits will outweigh the cost.

In this case, however, the imbalance between the physical and accounting realms was so vast that Shell is able to turn a profit from because of the $203 million it received from selling these phantom credits (shaded blue in the Revenue bar below):

Is it a wonder, then, that we become more cynical over these projects?

You may ask, why would the government offer phantom credits?

Well, the Alberta government could (and did) award subsidies to Shell to help it jump start the Quest program.

But by awarding phantom credits, it also saved about $200 million because by magically creating these carbon credits out of thin air, the buyers of these credits (oil sands producers like Chevron, Canadian Natural Resources, ConocoPhillips, Imperial Oil and Suncor Energy) are essentially paying for it.

Isn’t that great? Well, yes, except that these companies are supposed to be paying for carbon emissions to be removed when in reality, nothing is removed. For a project that costs this much to build, you would expect that it actually does more capturing-and-storing instead of just accounting magic.

Is there any silver lining from this?

Well, kinda, if you consider that Shell initially asked for a three-for-one deal, but even the Alberta government thought that was too much and went for a two-for-one deal instead. Another silver lining, I suppose, is that the granting of free credits ended in 2022, as we all know that something this good will not last forever.

The FT news story (linked again here) of Shell’s benefiting from the sale of phantom credits is probably not the proudest moment for the Alberta government, but it did offer a rebuttal claiming that these phantom credits helped make CCS a reality.

Quoting the Toronto Star, here’s the government’s official response:

Alberta Premier Danielle Smith’s office called the report “a smear job by Greenpeace.”

“Alberta is a world leader in CCUS. While others were talking about CCUS as an abstract idea, we were putting in place a system that helped show the world that carbon capture works,” wrote Smith’s spokesperson, Ryan Fournier. “Launched in 2011, the program was a huge success and kickstarted major advancements in CCUS in Alberta. Thanks to this program, Alberta now has 12 million tonnes of carbon stored and two of the largest CCUS projects in the world now operating here.”

Shell, on the other hand, appears to be the shrewd party here benefiting from the deal. It is not likely to return the $200 million gained from selling these phantom credits, and at the same time it could continue to tout the Quest project as a world-class carbon capture facility to reduce emissions.

But before we wrap up, remember that five-million-ton per year target under Alberta’s 2008 CCS plan?

How has Shell’s world-class carbon capture facility fared?

The Quest project captured around 1.06 MT per year, and on Shell’s website it said that it has captured a total of 7.7MT as of end-2022. Averaging at about 1.1 MT per year, it is nowhere close to the 5MT target.

Despite that, the Alberta government has doubled down and set an even higher bar for CCS, with a 30MT target by 2020, 75MT by 2030 and 139MT by 2050.

To realize these lofty goals, how many additional free carbon credits must the government offer to incentivize companies to construct these CCS plants?

At the end of the day, most of us can probably tolerate the fact that there may be differences between accounting carbon credits and real carbon reduction in the physical world.

But no matter how you slice it, a 50 percent difference is really stretching it and asking too much of the audience.