Investing in Gender Diversity in Japan

GPIF allocates to not one, but two, separate domestic strategy promoting diversity. How has that worked out?

Gender diversity is a big topic in ESG. I recall a colleague once mentioned to me it is the ‘low-hanging fruit’ in improving corporate governance and research has shown that a more diverse group of employees generally leads to better company performance.

However, the objective of this post is not to argue about the merits of improving diversity. In the field of ESG, there is generally no iron-clad proof about anything. Look hard enough and you could easily find research to show that gender diversity does nothing for a company.

Instead, this week we will take a page from the playbook of one of the world’s largest asset owners on how they approach this topic. We will examine how Japan’s GPIF invests in the gender diversity theme in the country, which is known to be a laggard among developed countries.

GPIF’s investment approach is worth studying because as we will see later, its investment in gender diversity is sizeable; it takes a diverse approach; and it sends a strong signal to corporates to improve their gender diversity without sacrificing returns too much.

Let’s begin!

Closing the Gender Gap

As mentioned above, Japan has been notorious for scoring poorly in gender gaps ranking. However, GPIF has never shied away from ESG investing. Ever since becoming a UN PRI signatory in 2015, the asset owner has taken active steps in diverting assets into sustainable investing.

One of these areas that GPIF started investing in is on closing the gender gap in the workplace. In 2017, it announced it selected MSCI’s customised index, the MSCI Japan Empowering Women Index (cheekily named “WIN”), as its index of choice for the gender diversity theme.

GPIF cited Japan’s aging society as one of the key reasons it is investing into this index:

Due to the aging society in Japan, the companies with better gender diversity scores can withstand the long-term labor shortage risk by having access to wider talent pool. The index also aims to encourage more female employment among Japanese companies, so that the overall economic growth will be improved.

Fast forward to 2023, GPIF announced that it will allocate another JPY500 billion into another gender diversity index, this time by Morningstar. It also has a catchy name: “GenDi J”, or the Morningstar Japan ex-REIT Gender Diversity Tilt Index.

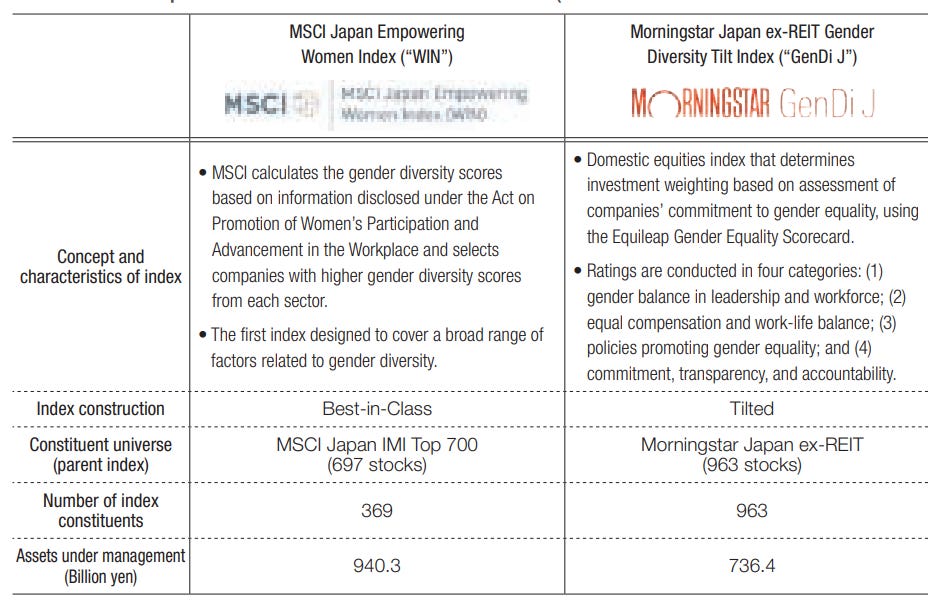

A quick comparison table on these two indices taken from GPIF’s 2023 Annual ESG Report below:

As we can see, the biggest difference between the two would be in their methodology and index construction. WIN is best-in-class, while GenDI J is tilted. As a result, WIN would have a higher tracking error to its parent (MSCI Japan IMI 700) compared to GenDi J’s tracking error to parent (Morningstar Japan ex-REIT).

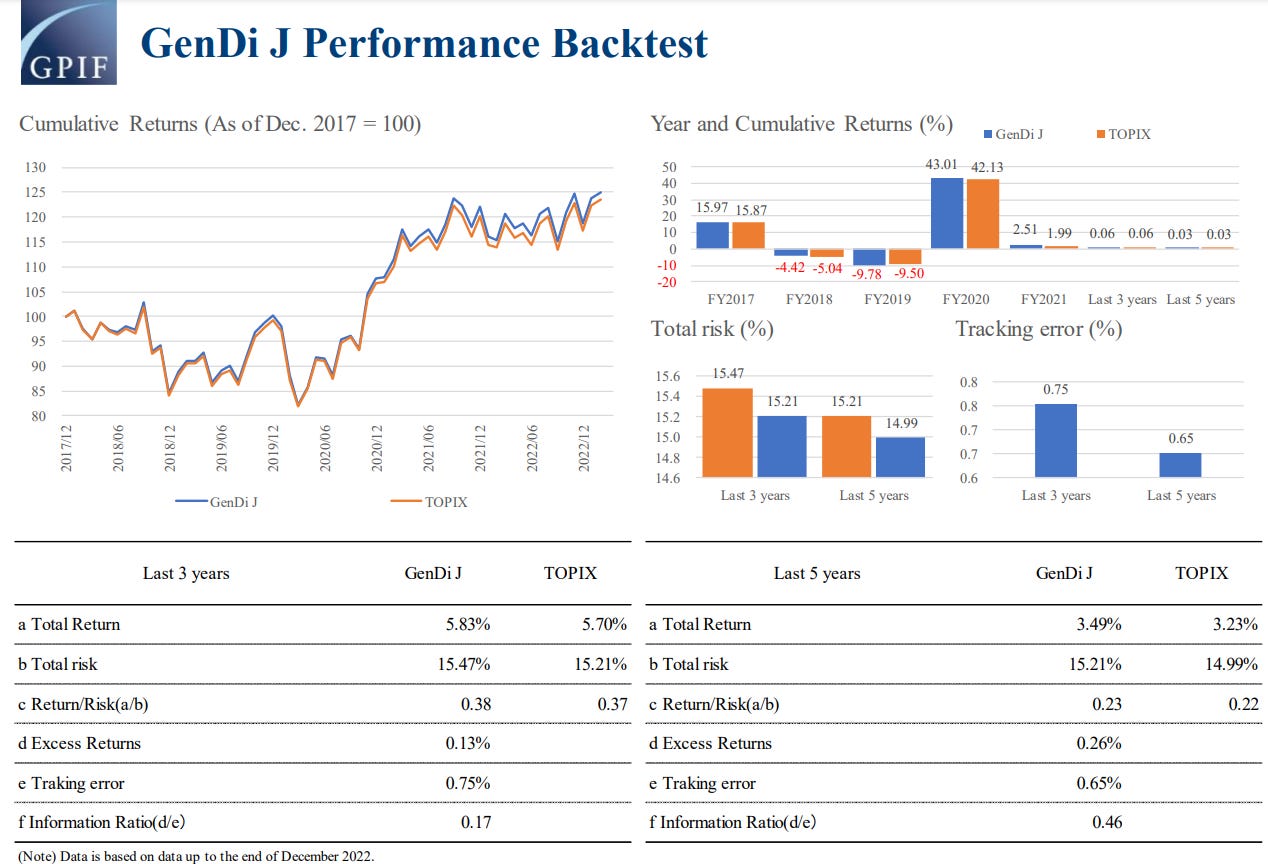

True enough when we look at the factsheets for both indices, tracking error for WIN is at 2.88% as of end-Oct 2024, while GenDi J’s tracking error hovers at 0.65-0.75% according to backtest performance (more on this later).

What this means in simpler terms is that WIN’s relative performance will be more volatile compared to GenDi J’s. In other words it may be the “riskier” choice to express one’s sustainability preference. There is nothing wrong with this but just know that with a higher tracking error, one is likely to see a larger deviation of performance (either positive or negative) versus its parent index.

Another thing to note is that GPIF makes sizeable investments in the gender diversity theme. Assets under management for WIN stood at 940 billion yen, while GPIF has 736 billion yen under GenDi J, despite the index being relatively new.

Index Performance

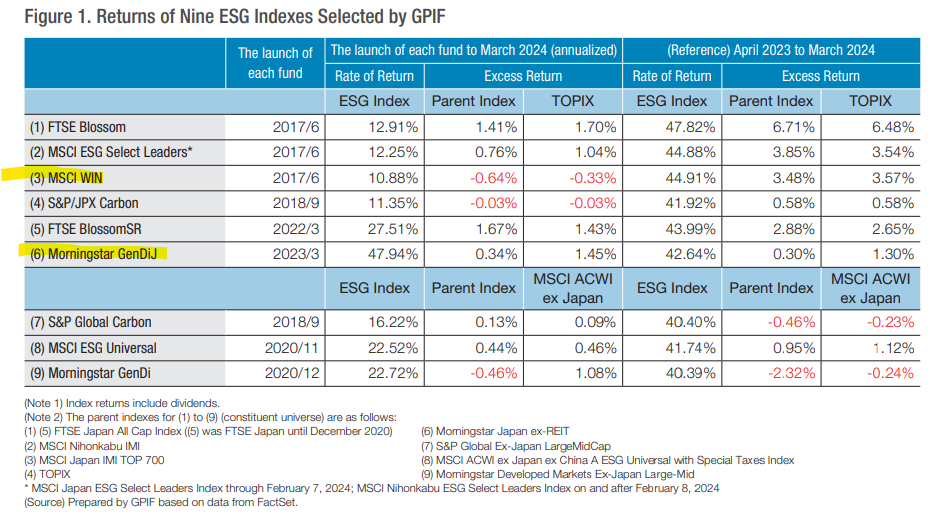

GPIF’s Annual ESG Report also reports performance for ESG indices that it invests in (up till March 2024). The table is reproduced below:

Looking at since-inception returns (annualised), Morningstar’s GenDi J has outperformed the parent index and TOPIX by 0.34% and 1.45% respectively. Recall that GenDi J’s tracking error to its parent index averages 0.65-0.75% in its backtest, so this performance deviation is within acceptable range.

MSCI WIN, on the other hand, saw an underperformance of 0.64% against its parent index. Given its wider tracking error, this is also expected somehow. From GPIF’s standpoint, there is no guarantee that an ESG index will outperform its parent, but what it could control is its risk tolerance, or how much of this deviation is considered acceptable.

What is really interesting here is the last three columns, which capture returns from April 2023 to March 2024. MSCI WIN absolutely destroyed the parent index with a 3.48% excess return, but before you conclude that this was the golden period for gender diversity, consider its sector allocation.

MSCI Japan Empowering Women Index (WIN)

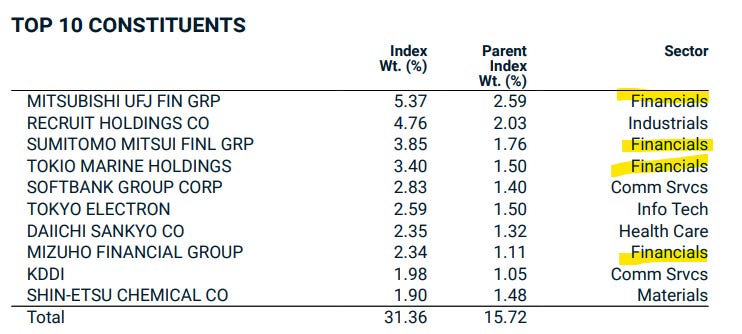

MSCI Japan WIN is heavily tilted towards financials (25.8% weight as of Oct 2024) compared to MSCI Japan IMI (13.4% weight), which makes sense as financials (banks, insurers, asset managers et cetera) are more likely to have more females in their workforce compared to more labour-intensive fields such as construction or industrials.

Here is a look at the top 10 constituents of MSCI Japan WIN:

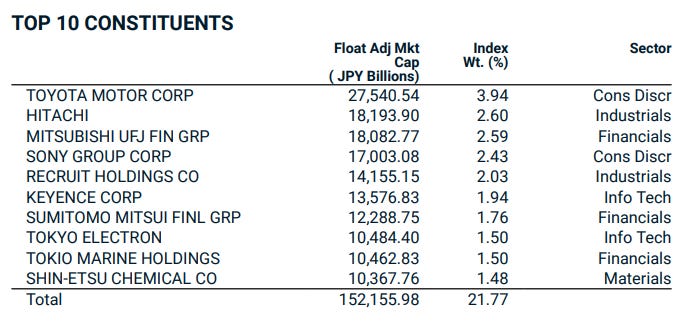

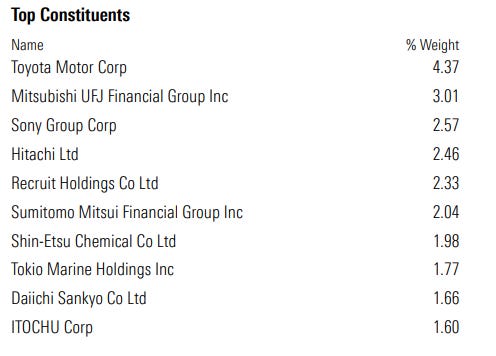

Compare that to the top 10 of its parent index (MSCI Japan IMI 700) — you may notice names like Toyota, Hitachi and Sony do not feature in the top 10 of WIN.

In other words, the March 2023 - April 2024 period could simply be a period where financials have done well (or the other sectors may have underperformed), which translates to the WIN index’s outperformance.

Morningstar GenDi J

Looking at the performance statistics below from the backtest, GenDi J’s tracking error versus its parent is at 0.65% for 3-year performance and 0.75% for 5-year performance.

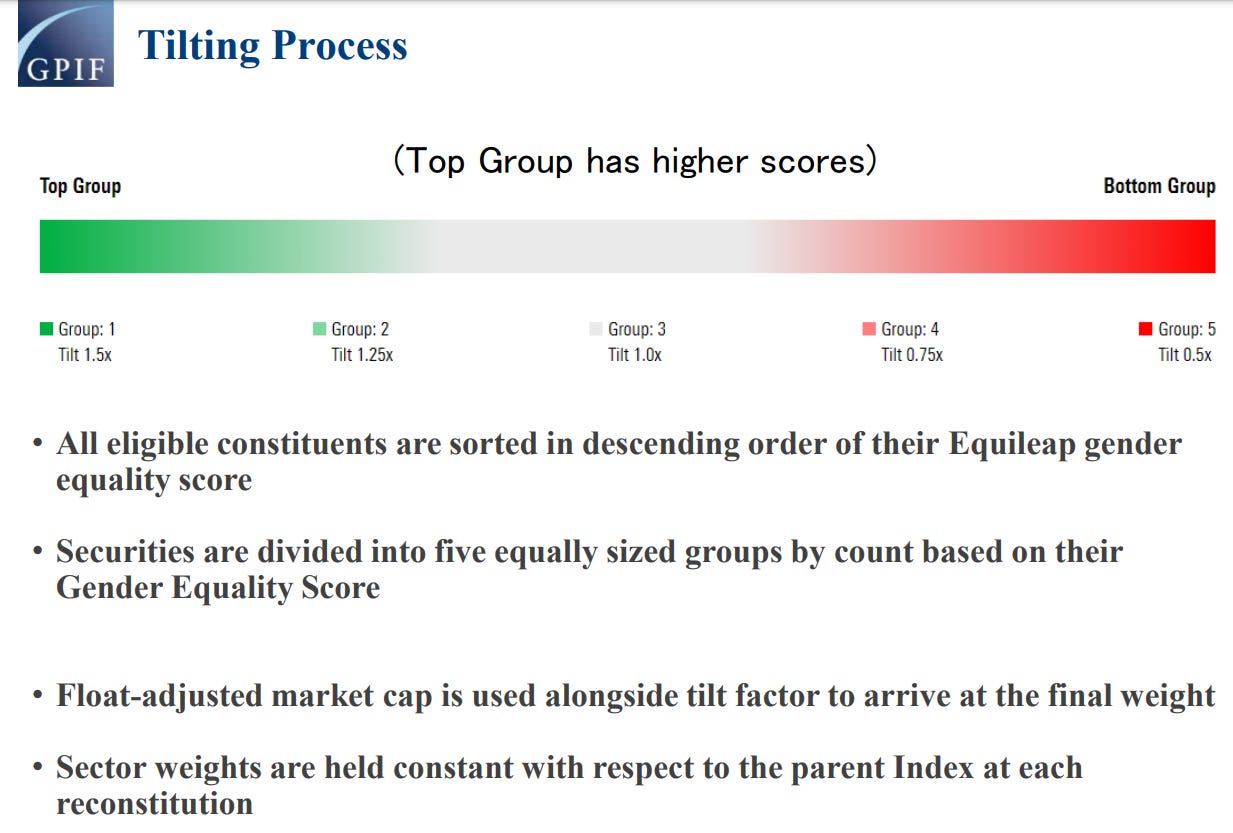

While MSCI WIN takes a best-in-class approach by selecting the companies with the best gender diversity scores for each sector and capping individual security weight to 5%, Morningstar’s GenDi J takes a “gentler” tilted approach.

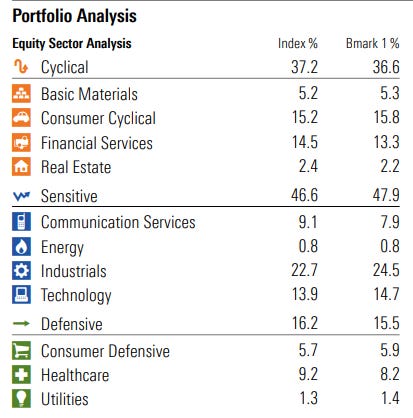

Under this approach, sector weights are neutralised relative to its parent, which reduces deviation in terms of sector allocation:

Looking at the top 10 constituents of GenDi J, we see a more “representative” list compared to MSCI WIN with Toyota, Sony and Hitachi back in the fold:

Summary

So, what did we learn from GPIF’s approach to investing in gender diversity?

Going back to what we said at the start, instead of paying lip service to how it believes gender diversity is important, GPIF actually made sizeable investments in this theme, which should be applauded.

GPIF’s investment vehicle of choice, utilising customised index, is also interesting. It also seems to be taking a diversified approach, utilising a bolder best-in-class approach and a gentler tilted approach to manage its overall tracking error.

Investment performance aside, one of the positive outcomes from GPIF’s commitment to gender diversity is the signalling effect this sends. It shows the asset manager’s serious commitment to improving gender diversity, which spurs companies to improve their diversity score to get on to these indices.

If you do a simple search, it is not hard to find Japanese companies issuing press releases announcing that it is a member of GPIF’s ESG indices, which shows that GPIF’s large investments have created incentives for companies to improve.

While Japan’s gender diversity scores still languish among developed countries, these small improvements could perhaps help to narrow the gender gap somewhat.

Japan is literally dying out because of women in the workplace, too long hours etc.