'Implausible' financial models underestimate climate risk

Weekly Newsletter (6 July 2023)

Happy Thursday! Welcome to this week’s Q-ESG newsletter.

What’s happening?

[1] Financial models underestimating climate risks, say actuaries

A paper by the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries and the University of Exeter finds a serious disconnect between current climate models used in financial services and reality.

Why this matters: One of the report authors, Professor Tim Lenton, notes that it is ‘concerning’ to see these models predicting low economic risks, adding that regulators and institutions should move towards more realistic scenarios. Read more from the FT here (account may be required).

[2] Big in Japan

Believe it or not — there is great demand for ESG bonds in Japan, with the 20-billion-yen ‘transition bond’ issued by Japan Airlines being six times oversubscribed.

Why this matters: Issuance of ESG bonds from Japanese companies and government-linked issuers soared 47 per cent to 2.6 trillion yen so far in the first half of 2023, according to Bloomberg data. The government is also planning to launch the world’s first sovereign transition bond some time this year.

[3] Mixed picture on ESG as results season draws to a close

Between political backlash against ESG in the US and continued support for ESG resolutions in Europe, the outlook for ESG investing remains mixed.

Why this matters: There remains a clear geographical split between Europe and the US on key ESG developments. Another important theme this year is oil companies — which have been sitting on piles of cash thanks to high oil prices — stepping back from previous climate commitments. Read more from Reuters here.

Explain to me like I am an eight-year-old

Climate scenarios

These are imagined case studies of what will happen to Earth in the event of extreme climate events such as heat wave or floods. Climate scenarios help us imagine the future and make plans to avoid the worst outcomes.

Books/papers/learning resources

Counterproductive Sustainable Investing: The Impact Elasticity of Brown and Green Firms by Samuel H. Hartzmark and Kelly Shue

This excellent paper by Hartzmark and Shue highlights that sustainable investors are too focused on percentage reduction in carbon emissions when they should have been more focused on absolute reduction.

This is aptly captured below:

Due to a mistaken focus on percentage reductions in emissions, the sustainable investing movement primarily rewards green firms for economically trivial reductions in their already low levels of emissions.

The paper uses two examples to illustrate this point: insurance company Travelers and building materials supplier Martin Marietta. Travelers emits 33,477 metric tons of carbon in 2021, or about 1 ton per million dollars of revenue. On the other hand, Martin Marietta emits about 5.1 million tons, translated to about 1,000 tons per million dollars of revenue.

Here is where the point really hits home: even if Travelers were to cut its emissions intensity by 100% (1 ton), it would only be equivalent to Martin Marietta cutting its emissions by 0.1% (1 ton divided by 1,000 tons).

If sustainable investors really care about reduction in emissions, should they not care more about the absolute level of reduction in Martin Marietta instead of rewarding high percentage reduction (which is the norm now)?

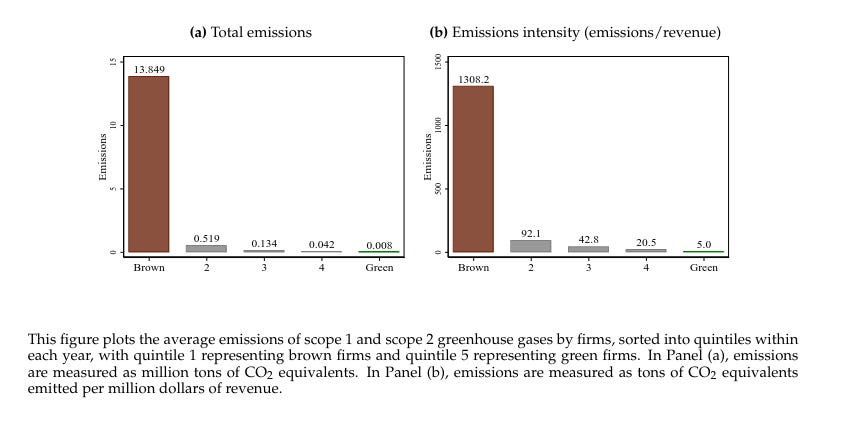

The charts below also illustrates how skewed emissions can be between brown and green firms. Note that the average emissions and intensity of brown firms are several orders of magnitude larger than the emissions of green firms.

The paper introduces a framework called impact elsaticity, defined below:

This measures a firm’s change in impact (for example emissions intensity) in response to a change in cost of capital. Generally, brown firms face a higher cost of capital compared to green companies.

More importantly, the authors show that brown firms exhibit a higher impact elasticity compared to green companies, which exacerbates the negative effect in response to a higher cost of capital.

This is often the result of sustainable investors “punishing” brown companies for being brown, but the irony is this worsens the companies’ financial standing and subsequently their emissions performance.

This is neatly summarized by the authors here:

Since transitioning to greener production by brown firms usually entails adoption of new equipment and technologies that differ from their existing brown investment projects, these new green investments are unlikely to pay off in the very short run and should be less attractive to firms in financial distress.

On the other hand, the actual impact elasticity of green firms is close to zero: there is really not much room for them to reduce emissions further, so sending capital their way is not going to help them cut emissions meaningfully.

In the paper, the authors also examine incentive effects: brown companies may be incentivized to become more green to have access to lower cost of capital.

Alas, the authors find that:

… changes in impact are measured in the wrong units. Sustainable investors appear to suffer from a proportional thinking bias in which they reward firms with large percentage reductions in emissions ratherwant than large level reductions in emissions.

In summary, this paper shows that the current sustainable investing framework is counterproductive because it starves brown companies of precious capital when they need them the most for a meaningful transition.

Meanwhile, the current system rewards companies based on the wrong units by looking at percentage change instead of absolute level.

We may be patting our backs on achieving large percentage reduction in emissions when in reality these reductions are quite trivial.

By directing capital away from brown firms and by measuring impact in the wrong units, we are missing the chance to make a real environment impact here, which is to reduce overall absolute emissions.